Defra’s Chief Scientific Adviser Gideon Henderson and I have written to the Veterinary Record to express our concerns about significant methodological flaws in a scientific paper it has published by Langton and colleagues1 on the effect of badger culling on cattle bovine TB (bTB) herd incidence

We do not believe the scientific methodology used is credible as the analysis has been carried out in an unusual manner that masks the effect of culling by incorrectly grouping data, which makes it impossible to assess the impact of culling on cattle TB breakdowns.

For each year analysed, Langton and colleagues combine data for areas where culling commenced that same year along with areas with a longer history of culling. This is an inappropriate grouping of data because it is known that the impact of culling on cattle outbreaks takes some time to appear,2 typically two years. The total area being culled has increased through the past seven years so, for each year analysed, a relatively large area of newly culled land, with a higher bTB incidence, is included in the total culled area in Langton and colleagues’ analysis.

This has the effect of masking trends in herd breakdown incidence like the statistically significant decreases observed previously3 in areas where culling has been underway for several years.

This flawed combination of data prevents Langton and colleagues from being able to assess their null hypothesis: that culling has no association with the incidence of Officially Tuberculosis Free-withdrawn (OTFw) herd breakdowns.

It is possible to reduce these problems and test the null hypothesis with a more appropriate analysis of the same type of data as used in Langton et al. Using the most recent published data,4, 5 we looked at cull areas by the year culling started, and assess breakdowns in these specific areas in subsequent years. Unculled areas are limited to those where no culling took place during the entire period being considered. Apart from this change in the grouping of data, we use similar assumptions as Langton and colleagues to enable a straightforward comparison.

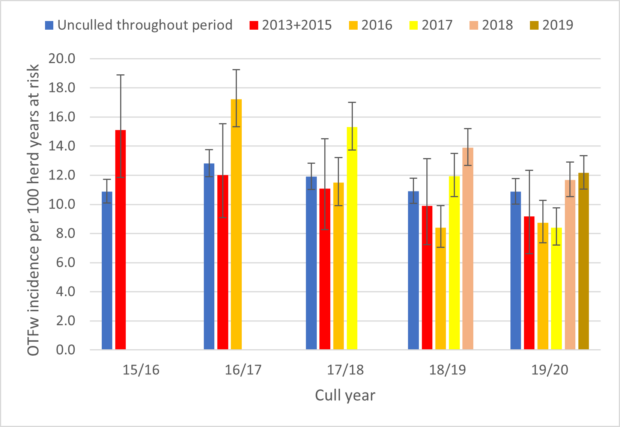

Our analysis indicates a clear reduction in OTFw cattle breakdowns, relative to unculled areas, in culled areas from cull year 2 onwards (Fig 1). For example, TB incidence in the areas where culling started in 2016 has dropped from 17.2 OTFw breakdowns per 100 herd years at risk in 2016/17, to 8.7 in 2019/20.

Similarly in the areas where culling started in 2017 it has dropped from 15.3 in 2017/18 to 8.4 in 2019/20.

In contrast, in the parts of the high-risk area (HRA) where no culling took place, incidence has only fluctuated slightly from year to year, from 10.9 in 2015/16 rising to 12.8 in 2016/17 before returning to 10.9 in 2019/20.

This analysis demonstrates the impact of the flawed approach of Langton and colleagues, negates the conclusion of that study, and indicates that badger culling is associated with a reduction of cattle TB cattle breakdowns in the HRA, as seen in previous studies.

In the second half of their paper the authors do not carry out any statistical analysis, simply stating that the peak of TB incidence does not coincide with the year the first cull started in a given county. Such group-level correlations are open to inferential errors through failing to account for confounding variables.

We agree with the authors that OTFw incidence is declining across the HRA, and that increased controls on cattle movements, testing and biosecurity will have contributed to this success. These are important components of our bTB eradication strategy. In the context of these increased cattle controls, we don’t regard it as surprising that incidence rates in an entire county do not alter on the date culling started in some parts of that county. As demonstrated by the analysis in Fig 1, culling in an area does correlate with subsequent decreases in OTFw incidence in that area.

More in-depth statistical analysis of the effect of badger culling on cattle TB incidence is underway at the APHA and will be submitted for peer-reviewed publication in due course. This will take into account differences between areas (including confounding factors) that can affect the measured impact of culling.

We appreciate that the badger cull is a controversial topic. It is important that this debate is informed by the best scientific analysis possible. More appropriate analysis of present data indicates the effectiveness of culling in the HRA in reducing cattle TB incidence.

Figure 1: Annual Officially Tuberculosis Free – withdrawn (OTFw) incidence in the high risk area of England from 2015 to 2020. The data used are the most recently published dataset4,5 and contain no additional information from that used by Langton and colleagues,1 except for inclusion of the most recent year of data (September 2019–August 2020). The blue bar represents areas where no culling occurred during the entire period. Other colours show areas where culling commenced in a particular year. Note, for instance, that areas where culling started in 2016 (orange bars) had high incidence when culling started, but significantly lower incidences than unculled areas in subsequent years. A similar pattern is observed for the areas that started in other years.

Figure 1: Annual Officially Tuberculosis Free – withdrawn (OTFw) incidence in the high risk area of England from 2015 to 2020. The data used are the most recently published dataset4,5 and contain no additional information from that used by Langton and colleagues,1 except for inclusion of the most recent year of data (September 2019–August 2020). The blue bar represents areas where no culling occurred during the entire period. Other colours show areas where culling commenced in a particular year. Note, for instance, that areas where culling started in 2016 (orange bars) had high incidence when culling started, but significantly lower incidences than unculled areas in subsequent years. A similar pattern is observed for the areas that started in other years.

References

1 Langton TES, Jones MW, McGill I. Analysis of the impact of badger culling on bovine tuberculosis in cattle in the high-risk area of England, 2009–2020. Vet Rec 2022; doi:10.1002/vetr.1384

2 Jenkins HE, Woodroffe R, Donnelly CA. The duration of the effects of repeated widespread badger culling on cattle tuberculosis following the cessation of culling. Plos One 2010;5:e9090

3 Downs SH, Prosser A, Ashton A, et al. Assessing effects from four years of industry led badger culling in England on the incidence of bovine tuberculosis in cattle, 2013–2017. Sci Rep 2019;9:14666

4 APHA. Bovine TB in cattle: badger control areas monitoring report. For the period 2013 to 2020. https://bit.ly/3CE6Y5P (accessed 10 March 2022)

5 APHA. Bovine TB epidemiology and surveillance in Great Britain, 2020 Bovine tuberculosis in Great Britain. Surveillance data for 2020 and historical trends.

This blog was updated on 24th May 2022 and 7th June 2022 to amend respectively the text and the graph related to the areas where no culling took place.

6 comments

Comment by Sue Wilson posted on

The Langton et al methodology is not flawed. The confidence intervals of overall TB incidence in cattle in both culled and non-culled areas (Langton et al – Fig 3) clearly show overlap in between culled and non-culled areas, regardless of the different lengths of culling in different areas, and therefore no significant difference. The prevalence in cattle (Fig 4) again shows overlapping CIs in early cull years 2013–15 and in 2019, but apparently higher prevalence in culled than in unculled areas 2016–18, with no overlap in the CIs. The Langton figures 3, 4 & 6 show an apparently declining trend in cattle TB from 2016/17 to 2019 in both culled and non-culled areas. Because better cattle measures (testing, biosecurity) were undertaken in culled areas along with badger culling, it cannot be claimed that any reduction in TB over the years (Langton et al. ’s Figs 3 &4 and Middlemass’s blog Fig 1) is due to the badger culling – and there is no positive evidence for the cull per se having any beneficial effect.

Furthermore, it has never been demonstrated (only “modelled”) that infections from badgers have resulted in herd breakdowns – cross-infection in the other direction (from cattle to badgers) is of course far more likely, via the vast amounts of infected cattle slurry and excreta contaminating the environment. The “cull” is a euphemism for what is brutal and inhumane slaughter of an iconic and sentient species, which should have no place in any civilised society.

Comment by Janet Henderson posted on

Very much agree with Sue Wilson's comment above. The policy of culling badgers appears to depend on poor evidence for consistent significant reduction in bTB. Reductions, where they occur, are assumed (not proven) to be connected with culling badgers. Where is the research comparing other factors that might reasonably be the cause of reductions? In most disciplines, failure to consider and give proper weight to other factors would be seen as a clear case of eisegesis. As I think the Chief Vet has acknowledged, killing thousands of animals (and doing it in cruel ways that cause suffering to the animals) is morally repugnant to growing numbers in our society. To do this without conclusive proof that it is effective is absolutely unacceptable. The farming industry must take responsibility to find a way to control bTB that does not require other species to carry the cost.

Comment by martin hancox posted on

Badger culls don't work, because badgers are not cause of spread of new breakdowns which are entirely within the cattle population. ISG 2007, found no effect in RBCT. Accumulated breakdowns, c. 1045, a third each no cull/ reactive/ proactive areas (Vial 2011). Reactive vs no cull areas, 356 vs 358 confirmed, 176 vs 178 unconfirmed, 76 vs 79 repeats , Lefevre 2005 .. only 311 TB badgers from 900 sq.km. / just 1204 spillover TB badgers in proactive areas. In the blog post Cumbria drop, but only 40 TB badgers out of 602 culled. NB. the halving of cattle TB, was Actually 2 years after the cull ended , 2007 ... merely normal 5-7 years of intensive testing.

SO, Middlemiss rightly admits that " the data presented are insufficient by themselves to demonstrate whether the badger control policy is effective or not in reducing bovine TB in cattle

Comment by martin hancox posted on

Since badgers have never actually been "the cause" of the spread of new unconfirmed and confirmed breakdowns , entirely within the cattle population, badger culls will have no effect on spread of cattle TB.

No self-sustaining reservoir of badger TB, the few actual TB badgers occur as a dead-end spillover ,just 1515 out of 11,000 badgers from 1900 sq.km. in the RBCT, just 400 from 576 sq.km. in Downs 2019

Costly Culls are unlawful and utterly meaningless !

m.hancox, ex-government TB Panel

Comment by Dr Brian Jones posted on

Naturally the CVO and Defra CSA are determined to undermine even peer-reviewed, published, science in order to justify an unpopular, expensive (for taxpayers), and inhumane policy. They will need to provide just as much actual data as Langton et al did before the graph above can be assessed. We await the publication of APHA's further in depth analysis after it has passed through an acceptable peer review process, but it must be said that APHA have to date been extremely selective in allowing cull data into the public arena. By hiding important information, such as precise boundaries of cull areas and even numbers of badgers killed in 2021, suspicions concerning political bias will remain.

Comment by Paul Torgerson posted on

When teaching veterinary students epidemiology and statistics, I always ask them to examine if the results of an analysis are biologically plausible. If not, then it might indicate an error in the data or analysis or the presence of some unknown confounding factor. In my scientific commentary (see Vet Record https://doi.org/10.1002/vetr.1603) of the manuscript by Langton et al,(https://doi.org/10.1002/vetr.1384) I reviewed evidence that suggests that there is very little direct contact between badgers and cattle. Further, detailed genetic and epidemiological studies indicates that, whilst transmission between badgers and cattle occurs, it is at a very low level compared to cattle to cattle transmission. This then asks the question whether the reduction in the incidence of OFT-W suggested by the CVO is plausibly due to the effects of badger removal, the majority of which are disease free.

On examining the data that is publicly available, I was unable to reproduce the OTF-W incidence in the ‘never culled’ area in 2019-2020. I calculated it as 10.9 per 100 HYAR on a cull year basis or slightly lower at 10.7 per 100 HYAR on a calendar year basis. This is someone less than the approximate 13.4 indicated in the Figure 1. that the CVO published in the Vet Record and above. According to DEFRA data the incidence in 2013 across the whole high risk area (HRA) was 14.7 OTF-W per 100 HYAR. This was the year that badger culling was initiated in the first 2 areas So the incidence has decreased from 14.7 to 10.9 or 10.7 (cull year or calender year basis) without the benefit of culling, although the non culled areas decreased over time due to the later commencement of culling in many areas.

In the press, DEFRA blogs and elsewhere, much has been made of valid comparisons between culled and unculled areas including controlling for the length of cull. There were also unjustified accusations of data manipulation. However, what is clear is that there is a continuing reduction in OFT-W incidence in areas that have not had badger culling. Thus to demonstrate the success of badger culling, data and its analysis has to overcome the substantial obstacle of distinctly demonstrating an additional reduction in OFT-W incidence in culled areas compared to the ongoing reduction of incidence in unculled areas. Such evidence is lacking as demonstrated by Langton et al.

Paul Torgerson PhD, VetMB, Professor of Veterinary Epidemiology, University of Zürich