The 6 July is World Zoonoses Day. This date has specific significance in that it marks the scientific achievement of Louis Pasteur, who successfully invented and administered the first vaccination against rabies in 1885. Rabies is still regarded as one of the most deadly zoonotic diseases. To celebrate the day, we have a message from the UK Chief Veterinary Officer (CVO), Christine Middlemiss:

CVO message – World Zoonoses Day

World Zoonoses Day is an annual opportunity for us to raise awareness of those diseases that can spread between animals and people and to celebrate global activities taking place to minimise the risks in the future. Zoonotic diseases such as avian influenza and rabies continue to have major effects on human health, animal health, livelihoods, and economies. Around 60 per cent of existing and emerging infectious diseases around the world originate in animals and slightly over 70 per cent of these zoonotic infections are caused by pathogens that originate in wildlife.

This year’s World Zoonoses Day comes amidst an unprecedented global health crisis caused due to the novel coronavirus causing COVID-19, a zoonotic disease in itself. Lessons learnt from animal disease outbreaks, such as surveillance, epidemiological reporting, and use of ‘hot spots’ to target later disease management have had a clear role to play in controlling the spread of this pandemic disease.

Environmental change and climate change

Predictions indicate that the human global population will increase to over 9 billion by 2050, 7 billion of whom will live in urban areas. As the human population increases and economies develop, so does the demand for food and other goods. Changes in land use, climate change, economic development, population growth and people living in densely populated areas are all contributors for zoonotic emergence. They alter risk pathways and enable pathogens to develop and transmit in new ways.

Climate change is also a major factor in zoonoses. Rapid changes to habitat due to unusual weather events such as heat, drought, flooding or wildfires are too rapid to allow ecosystems to balance sudden spikes in populations of species such as mosquitoes, known vectors for disease transmission. Some wildlife species are able to adapt, others are not; infectious pathogens will respond and take advantage of favourable situations.

Trade in wildlife and informal markets

Increasing populations, primarily urbanised around the world, leads to increasing demand for animal protein foods, such as dairy, meat and eggs and increased trade in wildlife and their products as food, use in traditional medicines and as pets. Changing agri-systems can lead to intensive, market-oriented livestock systems located close to urban areas, leading to an increased risk of viral spillover from wildlife contacts. Increased demand also favours informal food supply chains and informal markets, where live, wild animals are kept and sold. Viruses and other pathogens may be easily spread among animals that are kept close together; or to the humans who handle, transport, sell, purchase or consume them, when sanitary and protective practices are not followed.

Global activities and One Health

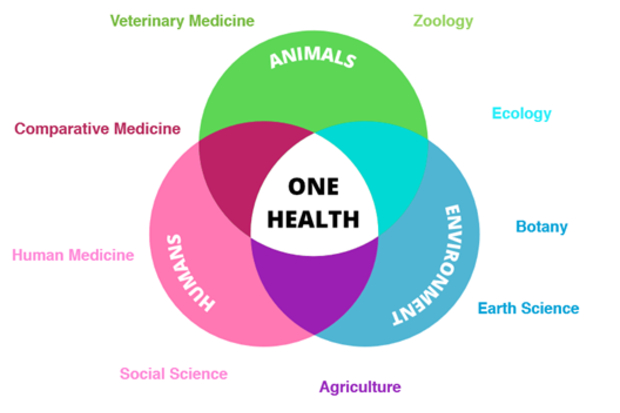

The Tripartite of the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and World Health Organisation (WHO) acknowledge that health issues at the human-animal-environment interface cannot be effectively addressed by one sector alone. Cooperation across all sectors and disciplines responsible for health is required to address zoonotic diseases and other shared health threats. This approach to working together is referred to as One Health. An excellent example of this was the use, in East Africa, of systems already in place to assist in the control of rabies being used to track and trace the spread of COVID-19.

Veterinary professionals have long worked in these interconnected spaces, recognised under the concept of One Health. This concept stresses the importance of understanding the interlinkages between human, animal, plant and environmental health and, more recently, for multi-disciplinary teams to work together on longer-term joint programmes as well as emergency responses. One Health programmes aim to develop ever-broader teams, including social scientists and behavioural scientists, using big data, risk management and communication to lead to more rapid and efficient outcomes from joint programmes.

The Tripartite last year published the ‘Tripartite Guide to Addressing Zoonotic Disease in Countries’. This year, they will be following this up with training at individual country level to assist in improving their systems and plans to prevent, predict and manage health threats at the human-animal-environment interface at subnational, national, global, and regional levels.

COVID-19 is a reminder that human health, animal health and environmental health are closely linked. Indeed they are integrated and we need to be too in how we approach them. Humans are one of about 8 million species of life on the Earth.

1 comment

Comment by udayavani posted on

nice article